Engman Public Natatorium, 1040 West Washington

The people who ran South Bend’s first indoor, city-owned swimming pool denied entry to African Americans for thirty years. Its transformation into the Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center is a powerful symbol of how the past must be bravely recognized and rectified.

Audio clip:

Audio transcript:

Click here to read audio transcriptBuilt in 1922, the Engman Public Natatorium was the City of South Bend’s first city-owned swimming pool. Despite the word “public” carved in its facade, the Natatorium denied entry to African Americans for fourteen years, then segregated people for fourteen more. As a taxpayer funded institution, the Natatorium became a focus of early 20th century civil rights action from a coalition of Black and white lawyers, politicians, and other professionals. The pool closed in 1978 and sat abandoned for almost thirty years before Indiana University South Bend students and faculty led neighbors, city leaders, and local non-profits to transform it into a place of learning, healing, and action against injustice for the 21st century.

As early as 1881, public calls came to reduce drowning deaths in South Bend’s St. Joseph River. The South Bend Tribune called a city natatorium to teach swimming “a necessity, not a luxury.”[1] Twelve years later, with no action and continued deaths, the Tribune wrote: “A crying need of South Bend is a natatorium. It has been talked of and written of and schemes have been proposed, but as yet nothing of the kind has developed.”[2]

In January 1919, at an address to the South Bend Chamber of Commerce, A.R. Erskine, President of the Studebaker Corporation, stated his belief that a natatorium is one mark of a city’s progress: “[W]e need more schools, churches and hospital facilities; also a natatorium or city bathing beach, and every other improvement we can possibly get to make South Bend an attractive, beautiful city.”[3]

Finally, in June 1919, the South Bend Common Council voted to build a natatorium. Two weeks after their vote, the South Bend Parks Board of Commissioners formally announced it would be built near the corner of West Washington and Chapel Streets, on land donated by Harry and Maude Engman.[4]

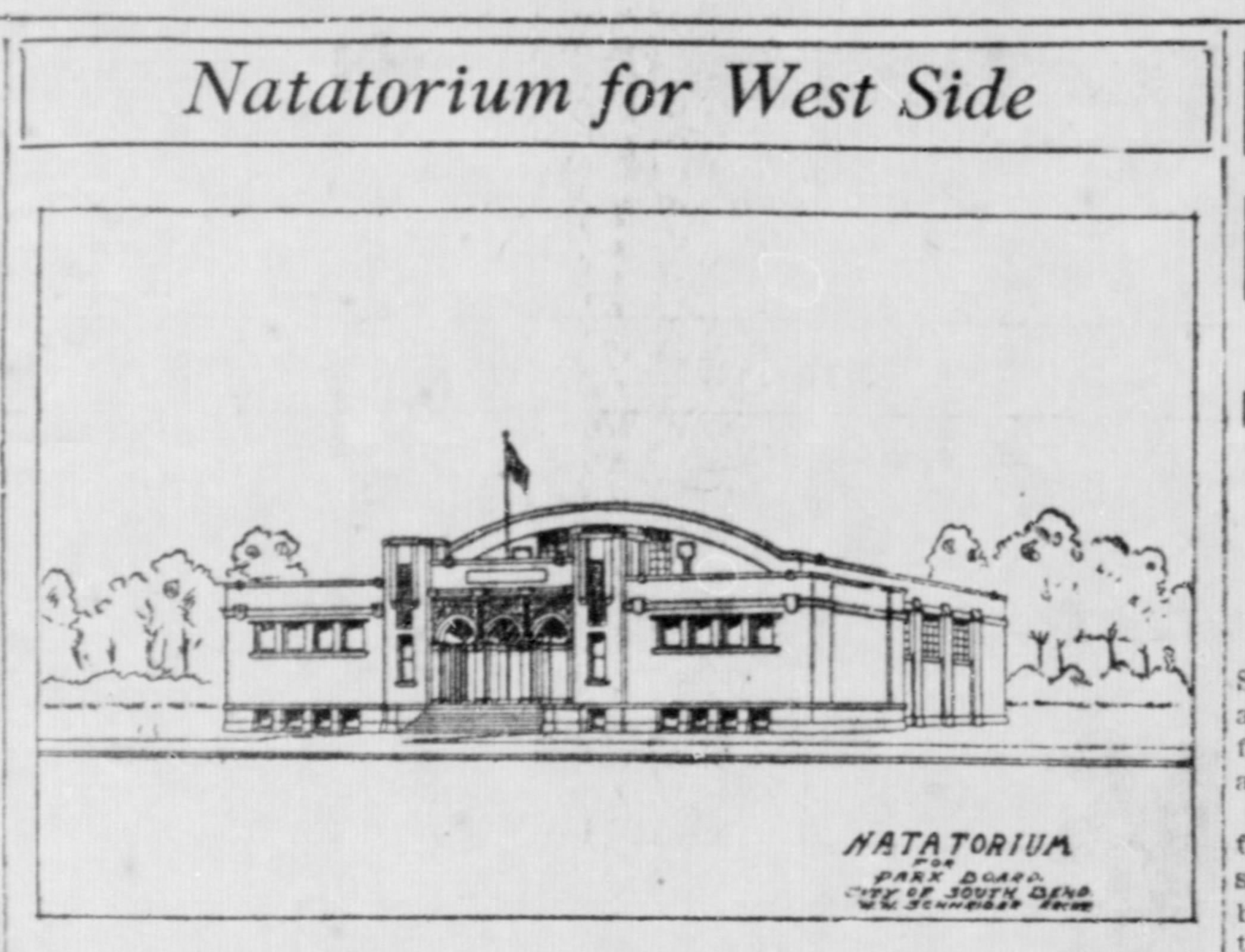

Natatorium for the West Side, South Bend News-Times, June 9, 1919.

The next several years saw the Natatorium’s construction hotly debated among city leaders and the well-to-do. Some were firmly in favor, but others did not support the idea. Some opposed the Natatorium out of ethnic prejudice, with the South Bend-News Time stating critics, “oppose the location due to the nationalities that hover in the neighborhood…”[5]

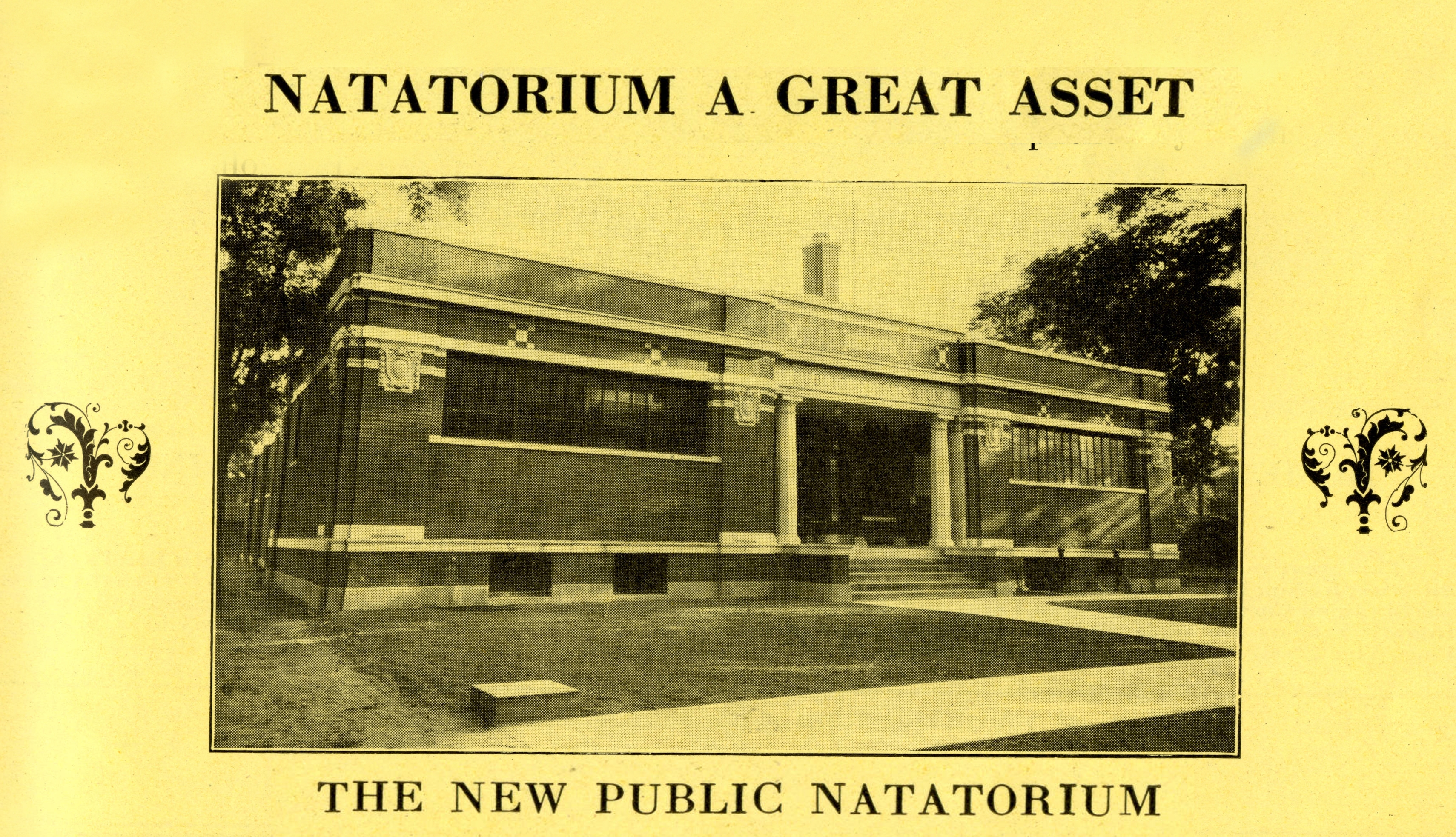

Despite the intense debate, on the evening of June 29, 1922, several hundred people attended a two-hour long public opening event of the new Engman Public Natatorium. By September, the Parks Board estimated almost 10,000 people took advantage of the brand-new facility.[6] A booklet entitled South Bend World Famed and published the same year listed the Natatorium as one of the reasons why people should move to South Bend, calling it “a great asset.”[7]

Not everyone had the opportunity to use this supposedly “public” asset, however. The people who ran the Engman Natatorium chose to institute a full ban on African American people. The full ban lasted fourteen years, when another fight over additional funding to fix the building provided leverage for local activists.

In 1931, the South Bend Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) challenged the natatorium’s racist exclusion with a petition delivered to the Parks Board, stating:

By reason of such exclusion of colored men, women, and children from the enjoyment and [comfort] of said Public Natatorium the colored populace has no safe place to which they may resort for the purpose of swimming… [People] are compelled to seek such dangerous opportunities for swimming as the nearby rivers, gravel pits, and so-called swimming holes… [A] youth of the colored group of this city did lose his life by drowning last summer while swimming in one of the abandoned gravel pits of this city.[8]

In October 1936, another petition was signed by thirteen African American taxpayers (including reporter and politician Jesse Dickinson), “on the ground that colored citizens are excluded from using the natatorium.”[9] Since the repairs to the building required significant additional taxpayer money, J. Chester Allen—one of the lawyers with the NAACP who signed the petition against exclusion—leveraged a state law requiring that city appropriations must be passed through the State Tax Board and that protests against any appropriation would be heard by the Tax Board as well.[10]

This brought in John Rothrock, representative of the Indiana Board of Tax Commissioners, to hear the case and arbitrate. He first stated:

I have never seen a city the size of South Bend that did not own and operate sufficient bathing facilities and that did not provide facilities for colored people. You have about 5,000 colored citizens here and they must be given a chance to swim, otherwise they will swim some place without protection.[11]

However, he then ruled: “I do not approve a plan to permit colored persons to use the natatorium at the same time as white persons, but I do think that a schedule should be arranged whereby the colored persons can use the pool.”[12]

The schedule allowed for segregated use only once per week, on Mondays. This was hardly full and equitable access, and it continued to reinforce racist ideas about Black and white human beings inhabiting the same spaces together.

Many people today have shared stories they heard that, after segregated days, the pool was drained to remove water touched by African Americans. For example, in a 2003 oral history interview, Coleridge Dickinson, son of Jesse Dickinson, shared, “We could go to the natatorium, but we could only go one day a week and that was on Monday before they cleaned the pool and let all the water out Monday night and filled it up again on Tuesday and Wednesday.”[13] Joseph Luten, an educator in South Bend schools, said:

I never went, see, but…I guess they would drain the water off and put fresh water in there so the others could come in the next day. I don’t know. I’m just saying that. I don’t know.[14]

During his oral history, Dr. Bernard Vagner remembered, “After the blacks used [it], they drained the pool and cleaned it and refilled it. That's just hearsay evidence. I don’t know anything about that, because I didn’t go to the Natatorium anyway.”[15]

Though many people had heard it as heresy and rumor, in a 2018 oral history, Robert Goodrich, director of the South Bend Parks Department in the late 1970s, and Paul McMinn, last director of the Engman Public Natatorium, addressed the subject. The Natatorium needed a minimum of three and a maximum of five to six days for water to drain, fresh water pumped in, chemicals such as chlorine (in use in public pools since 1910) carefully added, and then water tested to ensure safety.[16] Altogether, if the Natatorium were opened once per week for African Americans, it would need much of the subsequent week before white people would use it again.

Though it is hard to prove evidentially, the fact the rumor took hold is a consequence of the many daily reinforcements of the devaluing and dehumanization of Black lives by the white majority who were in charge of this pool.

Finally, in a February 1950 challenge at the meeting of the Parks Board, Attorney J. Chester Allen joined with other NAACP organizers including attorneys Zilford Carter, Charles Wills, and a white ally from the Jewish community, Maurice Tulchinsky, to threaten further legal actions if the Natatorium did not end their racist policy. The Parks Board acquiesced, voting that, “there is to be no race, creed or color discrimination at the Public Natatorium and henceforth attendance and classes, private classes excepted, will be open to all alike…”[17]

Though officially not allowed, some segregation did continue. Willie Mae Butts remembers it being around 1957 or 1958 that she tried to enroll her young son in a swimming class so he might be able to save her if she were drowning (she did not know how to swim herself). An employee first told her the class was full. She called back six weeks later at the start of registration for another class. The employee told her, “They haven’t given me the okay to enroll any colored kids.”[18]

By the 1970s, the Natatorium had operated for over fifty years. It was no longer “a great asset” like it was in 1922. It was smaller, significantly older, and less modern than the many other swimming facilities in South Bend. Paul McMinn, last director of the Engman Natatorium, remembered its final months:

We had repairmen coming all the time... It basically was on its last legs, and…the cost of just trying to keep it up, at some point...the ceilings and everything started to fall in.[19]

Also, for white children whose parents moved them to suburban subdivisions, private pools were increasingly affordable for middle and (especially) upper-middle class parents. City residents could also use the pools built in some of the newer public schools, such as Washington and LaSalle High Schools (present-day LaSalle Academy, only two miles from the Natatorium).

At a Parks Board meeting on July 10, 1978, members weighed the Natatorium’s anticipated $190,000 building repair costs plus $37,050 annual operating costs against the roughly $2,000 in annual ticket sales and came to a unanimous decision to close it.[20]

The Natatorium sat vacant and continued to crumble for decades.

Civil Rights Heritage Center institutional records, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

In 1993, the South Bend Heritage Foundation—a local non-profit community development organization—obtained grant money from the Historic Landmark Foundation of Indiana (present-day Indiana Landmarks) to do an engineering study. Jeff Gibney, celebrated director of South Bend Heritage, believed that if the building proved to have a sound structure, historic tax credits could be used to rehabilitate and reuse the Natatorium for some purpose.[21] Despite the group’s intentions, with no clear purpose forward, by 1999 the Natatorium came close to facing a bulldozer.

The Natatorium’s neighbors found their partner and savior from a coalition of students, faculty, and staff at Indiana University South Bend. The Civil Rights Heritage Center formed on campus in 2000 to “use the American Civil Rights Movement as living history to promote a better understanding of individual responsibility, race relations, social change and minority achievement.”[22] In 2005, Civil Rights Heritage Center historian David Healey submitted a three-page treatise titled, “The Natatorium Project,” proposing IU South Bend use the Natatorium as a historical, cultural, and outreach center.[23]

Partnerships formed between Charlotte Pfeifer, a representative elected to the South Bend Common Council; Alfred Guillaume, former Executive Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs at IU South Bend, who shepherded the students and faculty through the many institutional mazes; Gladys Muhammad, former Assistant Director for the South Bend Heritage Foundation; local architect Pat Lynch; and many others to reconfigure the site.[24] The City of South Bend, still the owner of the site, sold it to South Bend Heritage for $1 so they could lease and eventually sell it to IU South Bend, also for $1.

On May 23, 2010, almost 88 years after thousands of white people gathered to get their first tour of the brand-new swimming pool, a diverse crowd gathered to see it transformed. Hundreds marched along West Washington Street to see the Natatorium’s new purpose as a home to the Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center.

[CRHC.IR.244] Civil Rights Heritage Center institutional records, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

Then-Mayor Steve Luecke welcomed Barbara Brandy as the first invited guest. Ms. Brandy had told a story from when she was nine years old, wearing a red bathing suit her grandmother had made for her. She recalled arriving at the Natatorium and people staring at her as she tried to enter. She was turned away for coming on the wrong day.[25] Ms. Brandy became the first guest invited to enter so Mayor Luecke could offer her a formal apology on behalf of the City for the discrimination faced by her and thousands of others.

Ever since, people continue to gather at the transformed site. Instead of the sounds of swimmers and splashes echoing around the brick walls, what echoes today are the sounds of people talking with each other, confronting difficult histories, and building coalitions to directly challenge the systems that continue to oppress people. A place that exemplified the fight for early twentieth-century injustice is now a hub for action against early twenty-first-century injustice.

In August 2018, the City of South Bend’s Historic Preservation Commission—with a unanimous vote of the Common Council—designated the Natatorium a locally protected historic landmark, providing a strong legal framework against any major alteration or destruction of the building.

[1]The South Bend Tribune, January 18, 1881, 2.

[2] “Need of a swimming school,” The South Bend Tribune, June 21, 1893, 2.

[3] “Commerce Body Discusses Plans of Studebaker,” South Bend News-Times, January 31, 1919, 3.

[4] “Board May Build Natatorium Soon,” South Bend News-Times, June 9, 1919, 12.

[5] “Build the Natatorium (Opinion),” South Bend News-Times, June 19, 1921, 24.

[6] ““Figures Indicate Pool Has Gained Popularity,” The South Bend Tribune, September 10, 1922, 3.

[7] C.E. Young, ed., South Bend World Famed (South Bend, Indiana: Handelsman and Young, 1922), 40.

[8] Quoted in O’Dell, Katherine. Our Day: Race Relations and Public Accommodations in South Bend, Indiana. 1st ed. On Their Shoulders : Race Relations & Civil Rights in South Bend, Indiana. South Bend, Ind: Wolfson Press, 2010, 6.

[9] “Oppose $25,000 Fund To Repair Natatorium,” The South Bend Tribune, September 22, 1936, 9.

[10] “Indiana Swimming Pool Color Line Broken,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 17, 1936, 3.

[11] “State Orders City to Let Negroes Use Natatorium,” The South Bend Tribune, October 7, 1936, 5.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Coleridge Dickinson, interview by David Healey and Lester Lamon, September 23, 2003, Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center. https://archive.org/details/oh-dickinson-coleridge-2003-09-22_202101

[14] Joseph Luten, interview by David Healey and Michelangelo Basanio, November 13, 2001, Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center. https://archive.org/details/OH-Luten-Joseph-2001-11-13

[15] Dr. Bernard and Audrey Vagner, interview by David Healey and Sarah ??, March 10, 2003, Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center. https://archive.org/details/OH-Vagner-BernardAudrey-2003-03-10

[16] Paul McMinn, Robert Goodrich, and Robert Heiderman, interview by George Garner, April 11, 2018, Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center. https://archive.org/details/OH-McMinn-Goodrich-Heiderman-2018-04-11.

[17] O’Dell, 13-14.

[18] Willie Mae Butts, interview by David Healey, March 21, 2003, Indiana University South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center. https://archive.org/details/OH-Butts-WillieMae-2003-03-21

[19] McMinn, et. al., interview.

[20] Edmund Lawler, “‘Nat’ no more,” The South Bend Tribune, July 11, 1978, 20.

[21] Margaret Fosmoe, “Dreams still swim at 'The Nat' but the future has taken a dive,” The South Bend Tribune, January 29, 1989, B1-2; Rumbach, Dave. “Indoor Pool Getting Look for Possibilities,” The South Bend Tribune, July 6, 1993, B1.

[22] “Civil Rights Heritage Center Proposal [CRHC.IR.435],” Civil Rights Heritage Center Institutional Records, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

[23] “The Natatorium Project [CRHC.IR.145a],” Civil Rights Heritage Center Institutional Records, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

[24] There are so many additional people who championed and guided the transformation of the Natatorium than can be mentioned here. I want to ensure that at least a few of them are acknowledged, specifically Drs. Alma Powell, Kevin James, Monica Tetzlaff, and Les Lamon.

[25] Divided Waters. 2009, https://youtu.be/DMMrvyQmg5c