Linden School, 1522 Linden Avenue

A late nineteenth century South Bend school became the first to hire African American faculty and staff in the mid-twentieth century, then shut down after a lawsuit alleging racial segregation.

Audio Clip:

Audio transcript:

Click here to read audio transcriptIn the fall of 1890, 2,370 children ended their summers by returning to one of ten South Bend schools.[1] It is unlikely that any more than seventy-nine of those children were African American.[2]

Until 1869, African American students in Indiana had no guarantee that they could attend public schools. Previously, most African American students who were able to attend school went to a private one, perhaps one affiliated with a Black church.

Laws providing public education for African American students were proposed and repeatedly voted down despite favorable pressure by the Indiana State Teachers Association, among other groups. In 1869, the Indiana legislature finally passed a law requiring school trustees across the state to create a separate school for African American students if there was a large enough population of students to support one.[3]

During this time, South Bend likely did not have a racially segregated school. The small quantity of school-aged African American students suggests that parents who were able to send their children to school did so alongside white students. However, massive changes in the philosophy and structure of public education in the late nineteenth century, alongside massive movements of people from Europe to the United States as well as from southern states to northern states during the Great Migration, would eventually effectively segregate South Bend’s schools—though not officially.

With the incredible growth in population, existing South Bend school buildings were stuffed beyond capacity. School officials were well aware of the city’s growth and took steps to stay ahead.[4]

As early as May 1890, the (then appointed) Board of Education for South Bend’s schools responded to the growth in the northwest side of the city and publicly announced their intention to build a new school there. As the South Bend Tribune wrote, “The necessity for a new building in this section of our rapidly growing city has become imperative as many scholars residing there are compelled to attend one of the schools at a considerable distance, making the walk too long.”[5]

In 1890, a brand-new South Bend school joined nine others in admitting students. Linden school—which got its name from the street it was on—was located on Linden and Adams Streets and was to be a duplicate copy of the new Franklin School that opened only one year prior.[6] On June 14, 1890, work on Linden school began and moved quickly enough for it to be ready by the start of the new school year on September 1.[7]

Original Linden school before 1896 renovation. Courtesy The History Museum.

Linden quickly filled up. By October, average daily attendance was 110 with children in the primary through intermediate grades.[8] Once graduated from Linden, students could (if they chose) continue on to South Bend’s only high school, meeting students from Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Lafayette, Laurel, Coquillard, South, and Franklin schools serving the same grade ranges.

By the start of the 1894 school year, Linden’s enrollment increased to 135 students.[9]

By 1896, just six years after Linden first opened, local company H.G. Christman secured a contract to construct a four-room addition onto the existing building.[10] It doubled the capacity of the total space to eight rooms and made significant changes to the “old” part of the building as well.

Also in 1896, Linden welcomed its first kindergarten students. The kindergarten model came to South Bend from Bavaria (Germany) through the efforts of the women-led Progress Club and its president, Catherine Esmay. Ms. Esmay is credited as the first woman to hold public office in South Bend. The Progress Club engaged in a campaign that “made life uncomfortable for the members of the council for several weeks,” including “assailing” city council members “at their homes, places of business, on the streets, and everywhere one happened to come in sign of a Progress club committee [member].” Their bold tactics worked, as Ms. Esmay was selected by the all-white and all-male South Bend common council to serve on the school board.[11]

By 1902, Linden needed yet another remodel to accommodate more students. This time, the basement was converted into two additional classroom spaces.[12] It was still not enough to accommodate the incredible growth in South Bend and its student population. The following year, nearly 5,000 students attended one of thirteen South Bend schools—including 350 at Linden, over three times the number of students than when the school opened thirteen years earlier. It was considered “overcrowded beyond the limit permitted by the state board of health. Halfway through the 1921-22 school year, Linden expanded again—this time adding six additional rooms for a new total of sixteen.[13]

In all of the research done during the production of this piece, there were no indications of South Bend’s school corporation explicitly setting aside one school exclusively for African American students. Instead, the research shows a gradual transformation of some schools from predominantly white to predominantly Black. That transformation went hand in hand with the transformations in their respective neighborhoods, with thousands of African American people migrating to the city for factory jobs and forced to live in certain areas. However, intentional drawing of school boundaries by school officials amplified residential segregation to effectively gerrymander Black students. The student populations of a few schools became predominantly, if not overwhelmingly composed of African American students. Linden is the quintessential example of this transformation.

A July 1921 letter published in the South Bend Tribune revealed something about the children attending those schools. Signed only as “A Colored Citizen,” the unknown author cites incredible racial discrimination students experienced. As they wrote, “Colored children who attend white schools have but few moments, if any, in which they are not made to feel the white man’s prejudices, that they belong to an inferior race and that to be black is a disgrace.”

Despite this, in 1923, the South Bend Tribune revealed indications of the growing number of African American students at Linden. For example, the “Girl Reserves,” a group of young people organized through the YWCA, included the “Tri-H” group featuring African American students from Linden. Girls from Olivet A.M.E. church sang as part of the initiation ceremony.[14] More African American centered events and activities happened out of that space through the end of the decade. The newspaper records clearly show Linden school—and the surrounding area—as having a significant enough community of African American people to begin using the school as a community space.

In his 2010 oral history, Bernard Streets Jr., eldest son of educator and activist Odie Mae and Dr. Bernard Streets, talked about his time attending Linden from kindergarten in 1938 through ninth grade in 1948. He identified a radical shift in the Linden student population from his enrollment through his graduation, due largely to the second Great Migration of African Americans north during World War II. In his words:

When I started Linden school in the kindergarten in September of 1938, it was like, about, 90%, 85%, you know, white—10-15% black. By the time I graduated from Linden Junior High in June of ’48, it was about the reverse.[15]

Barbara Brandy attended Linden in 1948 as well. In her 2002 oral history, she confirmed and expanded on Bernard Streets Jr.’s experience at Linden:

The school was predominantly Black back in ‘48-‘49. It was getting that way because they were starting to have what you call ‘white flight’ in most of the neighborhoods. About the only whites in the neighborhood were the old Polish families or Hungarian families that refused to move because they were embedded in the community. And then a lot of them owned the grocery stores and the bakeries so, that was the thing.[16]

In the same year Mr. Streets and Ms. Brandy described Linden as being “predominantly Black,” South Bend school Superintendent Frank Allen confirmed their assessment by stating that 82% of Linden’s 369 students were African American.

Superintendent Allen delivered that statistic in response to pressure from a committee of Linden parents petitioning the Board of Education to address the incredible resource imbalance between Linden and predominately white schools. Additionally, parents wanted Allen to hire Black teachers to help alleviate the racial imbalance between the student and teacher populations.[17]

Superintendent Allen stated the board “never has opposed” hiring a teacher of color. This may or may not have been true; however, this does not satisfactorily account for why no teachers of color were yet hired. There were qualified African American teachers—undoubtedly. Why then had the corporation not hired anyone? Were there overt or covert pressures that kept Black teachers from applying? And if someone applied, why were none ever selected?

Despite the lack of accountability for the past, Superintendent Allen at least cracked open a door for the future by stating:

We will hire no teacher simply on the basis that he is either white or colored. However, if there is a vacancy in the Linden school and a Negro teacher applies who can meet state and city educational qualifications, we will consider him for the position.[18]

The Reverend John T. Frazer of Hering House responded to Superintendent Allen’s suggestion of waiting for a vacancy and a qualified candidate of color by stating:

I do not think it fair for a Negro teacher who does qualify to await the day when there is a vacancy in the Linden school before he or she will be considered for the position.

Rev. Frazer himself completed eighteen hours of college courses on education.

For the 1950 school year, the first two African American teachers in South Bend began their first days at Linden. Peggy Flowers Eskridge and Herbert Lewis Jr. were both graduates of Riley High School. Ms. Eskridge earned two additional degrees (bachelor's and master's) at Indiana University. Mr. Lewis earned his bachelor's at Western Michigan University.[19]

Ruby Jarrot Joyce joined them as the first professional staff member serving in the “department of pupil personnel.”[20]

None of these appointments were met with front page headlines. Ms. Eskridge and Mr. Lewis’ appointments were buried on page eight along with hundreds of other teachers assigned to various South Bend schools. The lack of fanfare for this historic debut is striking.[21]

By 1955, six African American teachers worked for South Bend schools—all at Linden.

The Progress Club—the same Club that previously pushed for the first woman to serve in public office and also for South Bend kindergarten classes—drew attention to this intentional segregating of South Bend teachers during a meeting of the St. Joseph County Council of Churches. The meeting featured over 100 local faith and social organizations and was attended by more than 450 people. Some attendees, including St. John’s Baptist Church’s Reverend Bernard White, commended the school corporation for hiring as many people as they did. Others, such as the NAACP’s Zoie Smith, would not commend the school corporation for relegating their African American teachers to only one school. The wide-reaching meeting also recommended setting up educational systems for migrating Mexican farmworkers, acknowledged discrimination against African Americans in both housing and retail, and recognized job discrimination experienced by Jewish people.[22]

By 1959, the South Bend school population was again growing too large for the existing physical structures to safely accommodate everyone. There were just under 22,000 students in the system, and an anticipated 7,000 more to come by 1963. They were already thirty-one classrooms short in 1959, and the School Corporation expected to be 135 classrooms short in the next few years if the growth trends continued as expected.

The core of Linden’s physical structure was among the oldest of South Bend’s school buildings, dating back to 1890. Despite its age, there was talk of yet another expansion. That talk was halted by a possibly well-intentioned, yet still deeply unnerving “urban redevelopment” effort from the South Bend Urban Redevelopment Commission to use federal funds to raze and rebuild not only Linden school, but several blocks of homes surrounding it.[23]

In November 1959, the South Bend City Council voted seven against two to devote $100,000 towards a study to completely clear and rebuild the area surrounding Linden.[24]

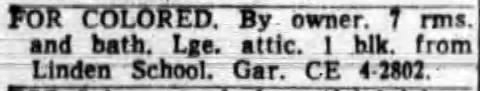

South Bend Tribune, November 27, 1959.

Homes, businesses, and other nearby structures (including Linden School) would be demolished and new public housing (along with a new school) built in their place.[25]

Over the following months, the pages of the South Bend Tribune relayed the criticisms of many of Linden School’s neighbors and supporters. In a February 1961 letter to the Tribune, local attorney Zilford Carter (who worked with others to challenge segregation at the Engman Public Natatorium) was clear in his disapproval:

It seems…that the bulldozers are coming to wreck and destroy and displace hundreds of families in the Linden area. This urban renewal and urban redevelopment is, in the final analysis, the destruction of homes. The people offended by the Linden area project have spent years toiling and struggling to pay for their homes. They are upset. Talking about building low rent housing projects to place these homeowners in and renting the projects to them instead of allowing them to remain in their homes that they have paid for seems unjust and unreasonable.[26]

Whether or not every home around Linden School was to be demolished or rehabilitated, the fact that even some homes could have been demolished was enough to cast the plan (and the planner’s understanding of the people living in the neighborhood) into doubt. Howard Warren, a Linden Avenue resident, explained it clearly:

Take a widow lady I know. She’s on social security. She owns a nice little house that’s worth maybe $3,000 on the market. She can’t get another house for $3,000. And she wouldn’t have enough money to rent or make house payments.

By September 1961, Linden residents’ resistance forced the Commission to call off the “clearance and rehabilitation” program.[27] While ultimately a win for those opposed to the program, one problem remained—the program would have funded a new Linden School.

By this point, Edward Myers, a 1945 graduate of Washington High School and later Wilforce College and Indiana University Bloomington, returned home to serve as the first African American principal in the district. First appointed interim principal in 1959 before taking over fully, Mr. Myers stayed with Linden through its final years.

Principal Myers, along with parents and supporters of Linden and other South Bend schools, would soon be drawn into a lengthy and passionate debate over the role of neighborhood schools in advancing—or detracting from—community integration.

Despite Linden becoming over 90% African American during the 1960s, the South Bend Community School Corporation moved forward with a second plan to replace the Linden School building—but maintain the school’s racial makeup. In 1964, the School Board approved funds to acquire fourteen homes just south of the existing school with the intention of razing those homes, building a new Linden school, and then demolishing the old one.[28] By this point, the core facility was the second oldest in the district.

The South Bend NAACP (including St. Augustine’s pastor Reverend Daniel Peil) and a new group called the Coordinating Council on Human Relations featuring the heads of twenty-one local human rights organizations, pushed to not reproduce a newer, yet still segregated Linden. In August 1965, the groups publicly chose Linden as the symbolic example of why the neighborhood school system needed to end, and a new, city-wide integrated school needed to be built. In a statement, the NAACP made clear that:

It was our expectation that the school board…would examine each of its decisions with a thought of mind that any whiff of segregation would be dispelled. Yet, new school buildings are proposed that will preserve, with brick and mortar, the racial separateness that is now, if not in deed at least in principle, alien to American ideals.[29]

They proposed what was known as the Princeton Plan. Each building would house the city-wide school population of a few grades. For example, all South Bend second and third graders at one building, ninth and tenth grades in another, etc. This plan would at least eliminate residential segregation, though other forms of segregation like student tracking, steering towards academic versus trade programs, disproportionate student discipline, and others would likely still occur.

There were also strong voices in favor of continuing Linden as a “neighborhood” school, possibly balancing the long-term ideals of integration against the immediate needs of an aging facility. In September 1965, Linden’s PTA president sent a letter to the School Board expressing their desire for a new building “without delay.”[30]

The school board made their position clear, formally resolving to continue the neighborhood system and build a new Linden school building (with the exact same 98.62% African American student population) for opening in the 1966-67 school year.[31]

Dr. Roland Chamblee, President of the South Bend Chapter of the NAACP, called the school board’s position, “unacceptable.”[32]

On October 26, 1965, white ally Thomas Singer, acting with the Coordinating Council on Human Relations, filed a federal complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Equal Educational Opportunities Program. Among the complaints cited was the fact that twenty-nine out of forty-nine South Bend schools had exclusively white teachers.[33]

The following spring, attorney Charles Wills and others representing nine Linden school children filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court against the School Corporation charging de facto segregation. The case, Copeland v. South Bend Community School Corporation, alleged that both the current and proposed building would both be highly segregated—99.4% African American out of an enrollment of 565. Six elementary schools within two miles had less than 50% African American student populations.[34]

Linden was now the focus of a tug-of-war between three competing forces.

In one corner, socially minded reformers from the NAACP, the Coordinating Committee on Human Relations, and other allied groups sought to correct massive racial inequality in South Bend by focusing on its earliest incarnation—our schools. They pointed out the School Corporation’s intentional drawing of district lines, their hiring practices, their resource allocation, and their inability to see their own complicity in perpetuating racial discrimination through their policies. If schools are responsible for shaping generations to come, then it made perfect sense for activists to focus integration efforts at our schools with the hope that the new generation would one day help solve other inequities such as housing, employment, policing, government, and everywhere else.

In another corner was the School Corporation. While they undoubtedly held their fair share of responsibility for inequalities in our school system, they were not directly responsible for racist housing policies, nor for hiring and employment structures outside their own.[35] That being said, choices were made by the School Corporation that resulted in so-call “neighborhood” schools with student populations that did not match the populations of their neighborhoods, nor the city as a whole. While those choices may have resulted in some happier white parents, African American students bore the burden.

Finally, a third competing force were the pragmatically minded parents of Linden. As the reformers pushed against the Corporation, pragmatic parents continued to watch their beloved children enter a crumbling physical structure. Unquestionably, the school was not maintained as well as others, and evidence of its dilapidated state would soon become undeniable.

In December 1966, Claudine Black was teaching her third-grade class in one of the basement classrooms. She heard a noise above her head and looked up quickly enough to realize the ceiling was beginning to buckle. As she made the realization, the fire alarm triggered. Fortunately, Ms. Black quickly and calmly moved her students out of the classroom because just as the last student exited into the hallway, the ceiling collapsed.

Within minutes, Principal Ed Myers inspected the damage. A photograph from the South Bend Tribune shows debris piled on top of the teacher's desk, knocking over and burying a small Christmas tree. Fortunately, no one was injured—though nerves were seriously frayed.[36]

The near tragedy did nothing to bring the different groups closer together. Some Linden parents saw this as proof of what they had been saying for years—the building needs immediate replacement. For them, bigger issues around equality could never be addressed if the school was literally collapsing. For the activists and the parents suing the School Corporation over segregation, this was proof that their children were being discriminated against with inferior and increasingly dangerous facilities.[37]

Finally, in September 1967, in the Copeland v. South Bend Community School Corporation case, judge Robert A. Grant accepted a settlement agreement between the School Corporation and the parents of the Linden children.

There would be no new building on the existing Linden school site.

The settlement also included a provision that the School Board “will expedite the adoption of a long-range school planning study [that will] take into consideration among other things the effect which any such building program will have on racial balance in our public schools and, to the extent consistent with sound educational policies, practices and procedures, the Board of School Trustees will seek to improve such racial balance.”[38]

Both the local and national NAACP backed the results. Reverend Lawrence Crockett, president of the local chapter, stated, “We believe that good faith implementation will lead to quality integrated education which will benefit all the public school children of South Bend.”[39]

Linden PTA President Odell Newburn, presumably frustrated with the six-month waiting period for the School Corporation to develop a new plan for Linden students, stated simply, “We’ve been put off and put off too long.”[40]

In May 1968, in response to the court settlement, the South Bend Community School Corporation finally unveiled a sweeping new redistricting and facilities plan dubbed the Educational Reorganization Plan.[41]

The original proposal created seven large junior- and senior-high school complexes fed from fewer, but larger elementary schools. Neighborhood lines would be redrawn to ensure no school had a Black student population higher than 40%. Ten older and smaller school buildings were to be abandoned—including downtown South Bend’s Central High School. Several of the feeder districts would build new junior high and other school buildings at a total cost of $28 million.[42]

Some schools would see radically different Black student populations. Navarre School would increase from a 1.3% Black student population to about 35%. Lafayette School similarly would increase from 1.72% to about 33%.[43]

All but two of the schools slated to be closed had a nearly equal to an overwhelming majority of African American students. Perley School (92.84% African American) was to be converted into a city-wide magnet school and capped at a 15% Black student population.[44] Franklin School (74% African American) was to become a city-wide school for students with special needs, again capped at 15% Black.[45] The former Studebaker School (planned to be added on and renamed to Riley Junior High School) and Oliver Schools were the only two near majority/majority Black schools that were not closed; however, their Black student populations would be significantly reduced from about 60% to 23% and 57% to 34%, respectively.

Although only roughly 1,800 students would need to be bussed under the plan, the burden of movement was undoubtedly placed more on Black students than white students. Though several overwhelmingly white majority schools would have a significantly smaller white majority under the plan, they remained majority white. Additionally, several other near completely exclusively white schools would remain so.

This was most starkly illustrated in the proposed Clay and Jackson feeders.

Of the schools in the Clay system—Clay Junior High, Clay High School (then in an older building that was to be replaced by a new high school), Eggleston, Swanson, and Maple Lane Schools (Darden would close and students would be distributed to the other schools), only Swanson would have any Black students: 0.11% of the student population. That was consistent with their previous enrollment.

Every school in the Jackson feeder system—Jackson High (present-day Jackson Intermediate), a newly proposed Jackson Junior High, Marshall, Hamilton, Hay, and Centre—had no Black students, nor would have any under the new plan.

Despite reservations, members of the local NAACP voted to accept the reorganization proposal.[46]

Other public reaction was decidedly negative. At an open meeting, parents of Navarre and Harrison students—where children from the Plaza public housing project (later renamed Rabbi Schulman apartments) would be bussed to—shouted down South Bend School Superintendent Holt with cries of “No!” and “Never!” To which the Superintendent had to reply, “Shouting will not help us.”[47]

A teacher at a high school outside the district (Penn High School) but who lived near South Bend’s Riley High School went so far as to establish a community organization to lobby opposition to the plan. James Cierzniak formed the Community Corporation for Educational Review. Cierzniak voiced his belief that Jackson and Clay schools should not continue to remain exclusively white as it placed too much of the “burden” on other schools whose Black student population would more dramatically increase. He also voiced a belief that the reorganization plan would make white residents “want to fly away from the city.”[48]

Cierzniak’s organization and their opposition is rooted in racist ideas that integrating African American students is a “burden” and, as Cierzniak was also quoted as saying, a “substantial threat to property values” by white people fleeing the inner city for the suburbs.[49]

Over the next several months, Cierzniak and his allies held informational meetings, took out a classified ad in the South Bend Tribune, and garnered media attention to galvanize others opposed to the plan.

Funding the $28 million reorganization and facilities plan required a property tax increase from $0.30 per $100 of estimated value to the state allowed maximum of $1.25/$100. It would more than quadruple people’s property taxes.

In early January 1969, the Indiana State Board of Tax Commissioners denied the School Corporation’s request for the maximum tax, instead allowing an $0.85 per $100 tax rate. This was a substantial increase; however, nowhere near what the Educational Reorganization Plan required to fund all of the new school buildings.[50] Without adequate funding, by February, school officials halted the reorganization plan.[51]

Once again, Linden’s replacement remained uncertain while hundreds of children continued to attend a building that many parents felt was unsafe.

In February 1969, South Bend school officials hired a six-member team of engineers and architects to inspect Linden. Their report acknowledged much needed repairs; however, they believed the school was structurally safe enough for children to attend.[52]

This was wholly unacceptable to almost all of the Linden parents. Odell Newburn spoke out on behalf of fifty-seven Linden parents in calling for a boycott. On March 3, 1969, 495 out of 527 students either called in sick or did not show up at all. Only eighteen arrived for classes.[53] Mr. Newburn and other parents held the boycott for a full week until their demand for an inspection by people not hired by the school corporation was met.[54]

Finally, on December 1, 1969, South Bend Schools Board of Trustees President Morton Linder released a statement announcing the final decision of the beleaguered Linden School:

It is the consensus of the board and the administration that the most appropriate site for this new elementary school—which we envision as an ultra-modern, unique and comprehensive facility—would be the present Kaley School site.

Kaley was about three-quarters of a mile away from Linden and had an African American student population of 55% before the reorganization plan.[55]

On September 29, 1970, school officials unveiled a bold new design for what would become Kennedy School. Two circular “pods” contained classroom space, with additional spaces attached including a new gymnasium, library, and a planetarium accessible by any city school. All of the former Kaley students and two-thirds of the former Linden students would combine, and boundary lines would be redrawn to create a “reasonable racial balance,” anticipated to be 65% students of color.[56]

Odell Newburn said he would urge parents to endorse the decision.[57] Perhaps wary of reigniting a messy public debate that would further impede Linden students getting a desperately needed new building, Eurilla Wills—elected both to the local and national leadership of the NAACP—described the new school as “a fully integrated school,” despite evidence to the contrary.[58]

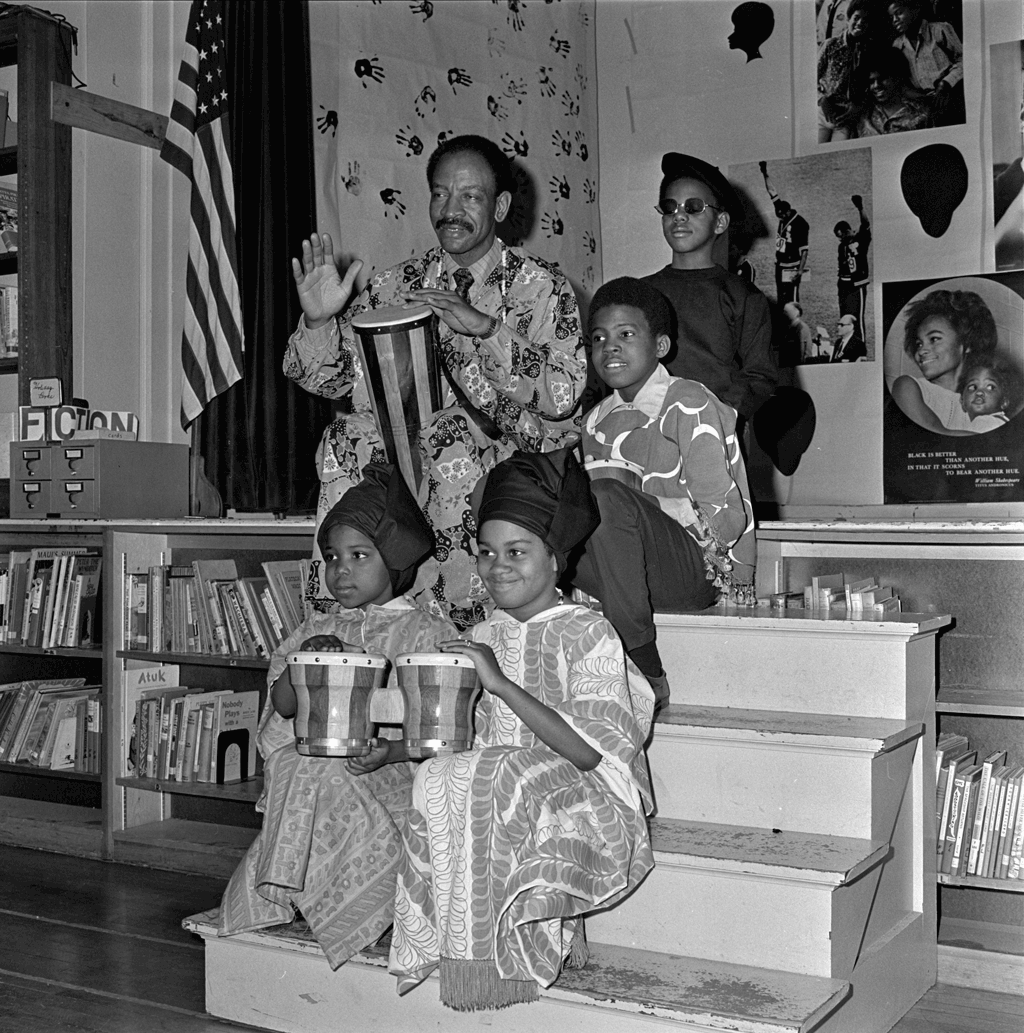

Linden parents waited an additional two years for construction to complete. Meanwhile, Principal Ed Myers and his teachers continued creating experiences for their students every day.

From the South Bend Tribune. Used by Permission.

Among many examples, in February 1972, he joined students for a celebration of Black History Week.

Finally, in June 1972, Linden’s halls no longer echoed with the sound of hundreds of local school children. Teachers packed up their classrooms for the last time. Linden officially closed, and after a summer break, on September 5, many former Linden students began classes at the brand new John F. Kennedy School.

Seven years of deeply divided community action finally yielded a new building, but not a radically altered racial makeup. While Linden’s Black student population was over 99%, nearly seventy percent of Kennedy’s students were African American.[59] This was far from the lofty goals of city-wide, non-residential based, fully integrated schools that activists had hoped for when they first targeted Linden.[60]

[1] “Attendance at the City Schools,” The South Bend Tribune, September 2, 1890, 4. It is worth noting that labeling all 2,370 as “children” may be inaccurate. People eligible for public schools ranged from six to twenty-one years of age. Some adults took advantage of these classes, particularly English language and trade classes. This may have been especially true for formerly enslaved African American people who were denied access to formal education by their enslavers. Since there is often no indication in the referenced articles what ages these students were, going forward I use “school aged,” “students,” or similar language rather than “children.”

[2] An 1887 enumeration of school-aged people in South Bend listed 79 African Americans. See “The City School Enumeration,” The South Bend Tribune, April 26, 1887, 2. The number of potential African American students may have been higher by 1890; however, as shown in a subsequent note, actual student enrollment in South Bend may have been only one-third of the potential student enrollment. Assuming the rate of attendance is similar for white and Black students, the potential African American student population in 1890 is unlikely to have grown in the three years from 1887 to a number high enough that one-third of actual students would be greater than 79. Regardless of the actual number, it is clear that the African American population as a whole and, by extension school-age people, was a very small percentage at this time.

[3] Ibid., 323. In places where there were not enough students to justify a separate school, districts could consolidate with each other in order to amplify numbers and allow a segregated school. If numbers of students “within a reasonable distance” were still insufficient to justify a separate school, school boards could use property tax funds to “provide such other means of education for said children.”

[4] For example, in the year before Linden opened, Franklin School opened to join then eight other school buildings. Located at the corner of Sample and Clinton Streets (near present-day Jefferson Intermediate), Franklin opened for students on what was then the southeast outskirts of South Bend. See “A New School Building,” The South Bend Tribune, April 18, 1889, 1; “Franklin School,” The South Bend Tribune, May 3, 1889, 1.

[5]The South Bend Tribune, May 27, 1890, 4.

[6]The South Bend Tribune, June 7, 1890, 4; “The City Schools,” The South Bend Tribune, August 30, 1890, 4.

[7]The South Bend Tribune, June 13, 1890, 4.

[8] “South Bend Public Schools,” The South Bend Tribune, October 2, 1890, 2.

[9] “Public School Enrollment,” The South Bend Tribune, September 5, 1894, 2.

[10] “Contract for a School Building,” The South Bend Tribune, April 2, 1896, 1. In 1909, Austin and Parker became Austin and Shambleau. They are responsible for several iconic South Bend buildings, including downtown South Bend’s Tower and South Bend Tribune buildings, the second Jefferson School (currently on Eddy Street), and many others.

[11] “A Woman In Office,” The South Bend Tribune, June 9, 1896, 4. See also “Miss Esmay Elected,” and “Gems of Thought,” The South Bend Tribune, June 10, 1896, pages 4 and 6.

[12] “Board of Education Meets,” The South Bend Tribune, September 19, 1902, 3.

[13] “Enrollment of Children,” The South Bend Tribune, September 16, 1903, 7; “Approves Bond Issue,” The South Bend Tribune, May 13, 1920, 19; “School Facilities of City Being Increased,” The South Bend Tribune, October 26, 1920, 6. Additionally, Linden implemented what was known as a “platoon” system to allow for much larger student bodies than would ordinarily be possible. Under this system, some students received classroom instructions while others were in the gym, auditorium, or outside. They would then rotate throughout the day. This system provided students with sorely needed physical and social activities (something sorely lacking with today’s data and testing driven focus), and also allowed for far greater student capacity. Between the physical expansion and the platoon system, Linden went from an “overcrowded” 357 students in 1921 to an estimated capacity of 840 by 1923. See “Study Population Trends,” The South Bend Tribune, December 30, 1923, 12.

[14] “Girls Reserves Hold Initiation ,” The South Bend Tribune, March 3, 1923, 5.

[15] Tetzlaff, Monica, and Muhammad Shabazz. Bernard Streets, Jr., April 26, 2010. Oral History Collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

[16] Lamon, Less, and Anne Petry. Barbara Brandy, April 2, 2002. Oral History Collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

[17] “Negro School Teachers Asked,” The South Bend Tribune, April 27, 1948, 13. In Ms. Brandy’s interview, Dr. Lamon asked her directly: “Any Black teachers?” Ms. Brandy replied, “Not when I was at Linden. No, the principal and everyone was white.”

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Teachers Get Assignments,” [ITAL]South Bend Tribune[/ITAL], September 3, 1950, 8.

[20] “Five More,” [ITAL]South Bend Tribune[/ITAL], September 10, 1950, 29.

[21] The lack of fanfare made it challenging for the author. Previous editions of this book falsely listed Mr. Lewis as the first and Ms. Eskridge as the second African American teacher. I sincerely regret this error and am glad to correct it moving forward.

[22] “Hiring Policies Given Town Meeting Airing,” The South Bend Tribune, February 14, 1955, Section 2, Page 1.

[23] “School City Aims to Keep Costs Down,” The South Bend Tribune, January 11, 1959, Section 2, Page 1.

[24] “Annexation Bill Passes City Council,” The South Bend Tribune, November 24, 1959, 22.

[25] “US Ok Assured for Linden Project,” The South Bend Tribune, January 17, 1960, 18; “City Studies Outlay of $12 1/2 Million,” The South Bend Tribune, November 27, 1960, Section 2, Page 1.

[26] “Letter: Disturbing,” The South Bend Tribune, February 23, 1961, 4.

[27] “Central Area Study Urged by Officials,” The South Bend Tribune, September 7, 1961, Section 3, Page 1.

[28] “Funds OK'd for Linden School Site,” The South Bend Tribune, November 3, 1964, Section 2, Page 1.

[29] Roger Birdsell, “Linden Area as Drive Symbol,” The South Bend Tribune, August 17, 1965, 15.

[30] Roger Birdsell, “Linden PTA Wants New School Built,” The South Bend Tribune, September 8, 1965, Section 2, Page 1.

[31] Roger Birdsell, “Neighborhood Unit is 'Education Base',” The South Bend Tribune, September 19, 1965, Section 2, Page 1.

[32] Roger Birdsell, “Board to Proceed with Linden Plans,” The South Bend Tribune, October 15, 1965, Section 2, Page 1.

[33] Roger Birdsell, “School Board Tells of Racial Complaint,” The South Bend Tribune, December 22, 1965, 17.

[34] “Federal Suit Filed by Linden Parents,” The South Bend Tribune, April 20, 1966, 29.

[35]That being said, the School Corporation also did not articulate an activist or anti-racist stance. Quite the opposite, in fact, often capitulating to white supremacy. For example, in June 1966, School Superintendent Jardine was quoted as saying that busing students from one neighborhood to another was not a solution because “mixing children of different backgrounds and abilities reduces the achievement level of all of them and hinders the effectiveness of their instruction”. See Laurance Morrison, “Peil Lists Linden School Proposals,” The South Bend Tribune, June 2, 1966, 27.

[36] Roger Birdsell, “Linden Students on Long Holiday,” The South Bend Tribune, December 11, 1966, 1.

[37] Judge Robert A. Grant denied their motion.

[38] Roger Birdsell, “Settle Linden Suit,” The South Bend Tribune, September 13, 1967, 1.

[39] “Linden School Plan Praised,” The South Bend Tribune, September 13, 1967, 1.

[40] Roger Birdell, “Linden PTA Official May Call Boycott,” The South Bend Tribune, September 22, 1967, 21; “Holt Reaffirms Linden Decision,” The South Bend Tribune, September 27, 1967, 50.

[41] Roger Birdell, “School Plan is Announced,” The South Bend Tribune, April 5, 1968, 23. The plan contained three stated goals: 1. “Achieve a more effective and efficient educational program for all boys and girls in the corporation.” 2. “Eliminate old school buildings that are costly to maintain and not adequate for modern needs and to plan new buildings to meet present and future requirements.” 3. “Reduce racial imbalance throughout the corporation.”

[42] Roger Birdell, “Unveil Huge School Plan,” The South Bend Tribune, May 16, 1968, 1.

[43] Roger Birdell, “School Plan Meets Violent Opposition,” The South Bend Tribune, June 5, 1968, 33.; Roger Birdell, “3 Revisions Are Made in School Plan,” The South Bend Tribune, July 23, 1968, 17.

[44] Two tables on pages 16 and 17 of the May 16, 1968 issue of the South Bend Tribune show the anticipated impact of the original reorganization plan. This plan would be significantly modified later, and so numbers should be reviewed carefully. Central High School had a 48.56% Black student population and Kaley had 49.25%—both were slated for closure. Though not quite majority Black, it was significant enough to be added to the other overwhelmingly Black schools that were also closed.

[45] Considering this school was intended for students with intellectual disabilities, it is curious why School Corporation officials chose to institute a cap on Black enrollment at 15%. What would happen to those additional students beyond the 15% cap, and was there a similar obstruction for white students with disabilities?

[46] “Some Parts of Proposal Win Backing,” The South Bend Tribune, May 30, 1968, 19.

[47] Roger Birdsell, “School Plan Meets Violent Opposition”.

[48] “Citizen Group Forms to Fight School Plan,” The South Bend Tribune, July 7, 1968, 21; “Group Vows to Oppose School Shift,” The South Bend Tribune, July 9, 1968, 15; Roger Birdsell, “All-White Jackson School Issue Aired,” The South Bend Tribune, May 25, 1968, 1.

[49] “Group Vows Fight On School Changes,” The South Bend Tribune, July 10, 1968, 34.

[50] “Building Fund Cut Jolts City Schools,” The South Bend Tribune, January 22, 1969, 27.

[51] Paul Lamirand, “ERP School Plan Delayed,” The South Bend Tribune, February 14, 1969, 19.

[52] Paul Lamirand, “Linden Tour of Inspection on Saturday,” The South Bend Tribune, February 4, 1969, 17; Paul Lamirand, “Linden Inspection Team Tours School,” The South Bend Tribune, February 9, 1969, 23; Paul Lamirand, “Linden School Reported Safe, Sound,” The South Bend Tribune, February 25, 1969, 15.

[53] Paul Lamirand, “Linden Classrooms are Nearly Empty,” The South Bend Tribune, March 3, 1969, 13. ,An additional fourteen attended a special study session held at the Hansel Center.

[54] William Stoner, “Inspectors From State Tour Linden,” The South Bend Tribune, March 6, 1969, 25; Paul Lamirand, “New School Fight to be Continued,” The South Bend Tribune, March 9, 1969, 23. While Mr. Newburn was convinced, not every parent followed his lead.

[55] Paul Lamirand, “Kaley Named Site of New Facility,” The South Bend Tribune, December 2, 1969, 19. Colfax School on Lincolnway West with a 64.5% Black student population was to be abandoned as well.

[56] Paul Lamirand, “Unique School Plant Proposal Unveiled,” The South Bend Tribune, September 30, 1970, 17; Paul Lamirand, “School Suit Settlement 'Not Broken',” The South Bend Tribune, October 6, 1970, 17.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Paul Lamirand, “NAACP Likes Kennedy School Plan,” The South Bend Tribune, January 16, 1972, 23. African American students constituted at least 15% of the entire school population. It is difficult to justify the difference between 15% and 65% as a “reasonable racial balance.”

[59] Paul Lamirand, “Kennedy District Plan Awaited,” The South Bend Tribune, March 19, 1972, 29.

[60]Parents, community members, school officials, and many others with a vested interest in South Bend’s school children continued to clash on integration well into the twenty-first century. In 1980, another lawsuit, Brookins v. South Bend Community School Corporation, ended with a formal consent decree with the Department of Justice imposing limits on the African American student population at any school. That consent decree is in place as of this writing, and several South Bend schools are out of compliance. Another racial integration plan in 2000, Plan Z, again reorganized schools. Kennedy was among those affected. Instead of a neighborhood school as activists like Odell Newburn and others voiced strong support for, and instead of an agent of city-wide change as the NAACP and other activists fought in court for, Kennedy became a city-wide magnet school where students must take a test in order to gain admission.