Olivet AME Church, 310 W. Monroe and 719 N. Notre Dame Ave.

South Bend’s first and oldest African American centered church has engaged generations for over 150 years.

Audio Clip:

Audio transcript:

Click here to read audio transcriptFounded in 1870 by the Reverend John Bundy and a small group of early South Bend citizens, Olivet African Methodist Episcopal is the first local church to center African Americans in worship. From its founding through today, Olivet continued to connect South Bend’s community to each other and to educate people about the broader issues surrounding them.[1]

Two of the church’s nine charter members began an incredibly long legacy in South Bend—Rebecca Maria (Bass) Powell, and her husband Farrow Powell. They were the first people of African descent in South Bend to establish a long family line that existed into the twenty-first century.[2]

Though the Powells were not the first people of African descent to live in South Bend, the African American community they found was relatively small. The 1850 census lists only eighteen African American people out of a total population of 1,652—about 1.1% of the city’s population. By the 1870 census that number had grown significantly to a total of seventy-three—still less than 2% of the city’s population. Though still reasonably small, the community had undoubtedly grown large enough to support services like a church.

In 1870, nine charter members, along with the Reverend John Bundy, organized the first known worship organization for or by African Americans in South Bend. Five of the nine charter members were part of the Powell family—Farrow and Rebecca, son John Powell, and daughter Catharine and her husband James Jackson. On March 16, 1872, Farrow and his son-in-law James signed papers legally incorporating the organization as the “Olivet Chapel Society of the A.M.E. Church in South Bend.” [3]

South Bend Tribune, May 25, 1872.

By December 1872, a new church building was ready for worshippers.[4] From its earliest days, Olivet was a center for local African American history, culture, and community. As early as 1873, they sponsored public events featuring intellectual discussions, music performances, and guest lecturers from around the U.S. and the world.

For example, Sojourner Truth, the legendary abolitionist and activist, lectured at Olivet. On October 6, 1873, she delivered a speech entitled, “The Condition of the Poor Colored People in the South.”[5]

As early as 1878 and continuing well into the twentieth-century, Olivet not only welcomed lecturers sharing information about Africa, but welcomed African pastors as well. In 1888, Reverend A. H. Meves of Haiti and a graduate of Wilberforce University took over as pastor.[6] He is one of at least two people born outside of the United States to serve Olivet.[7] In 1932, Reverend H.N. Tantsi from Queenstown, South Africa, became pastor.[8] During his time, Rev. Tantsi offered lectures about the continent including, “Africans—Their Customs and Habits” and “Africa, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.”[9]

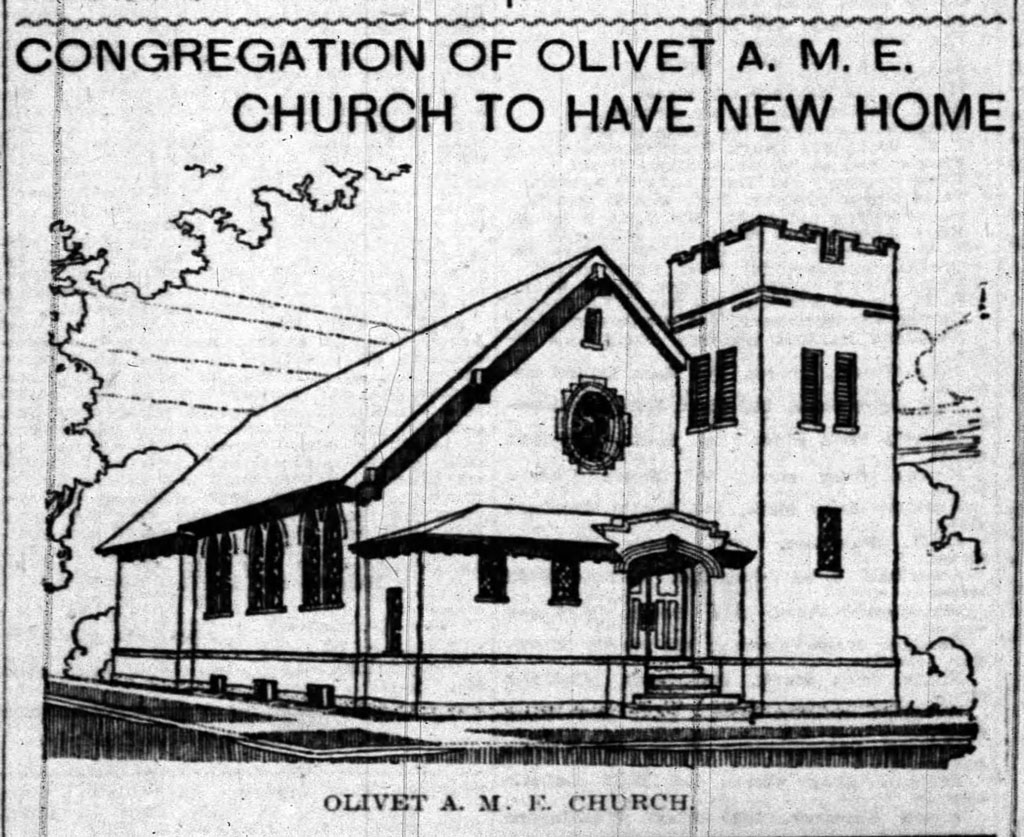

In April 1916, after years of fundraising to secure $9,000 (roughly $213,000 today) in donations for a new building, then-pastor Reverend Dr. C. Emery Allen announced that construction on a new facility was ready to begin.[10]

South Bend Tribune, April 8, 1916.

Reverend John Bundy, Olivet’s very first pastor in 1871, returned to South Bend to hold a farewell service in the church he helped establish.[11] On Sunday, February 4, 1917, regional church leaders joined local members to dedicate their new building.

South Bend Civil Rights History collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center Collections, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

South Bend Civil Rights History collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center Collections, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

Olivet soon returned to offering the same variety of intellectual, spiritual, musical, and other community activities they had previously. For example, in September 1917, Olivet welcomed Dr. Richard R. Wright, Jr., editor of the A.M.E. newspaper, The Christian Recorder, and an early graduate of the burgeoning field of sociology—in fact, he was the first African American person to earn a PhD in sociology. Recognizing the early years of the era later called the Great Migration, Dr. Wright titled his lecture, “The Meaning of the Recent Migration of Negroes to the North.”[12]

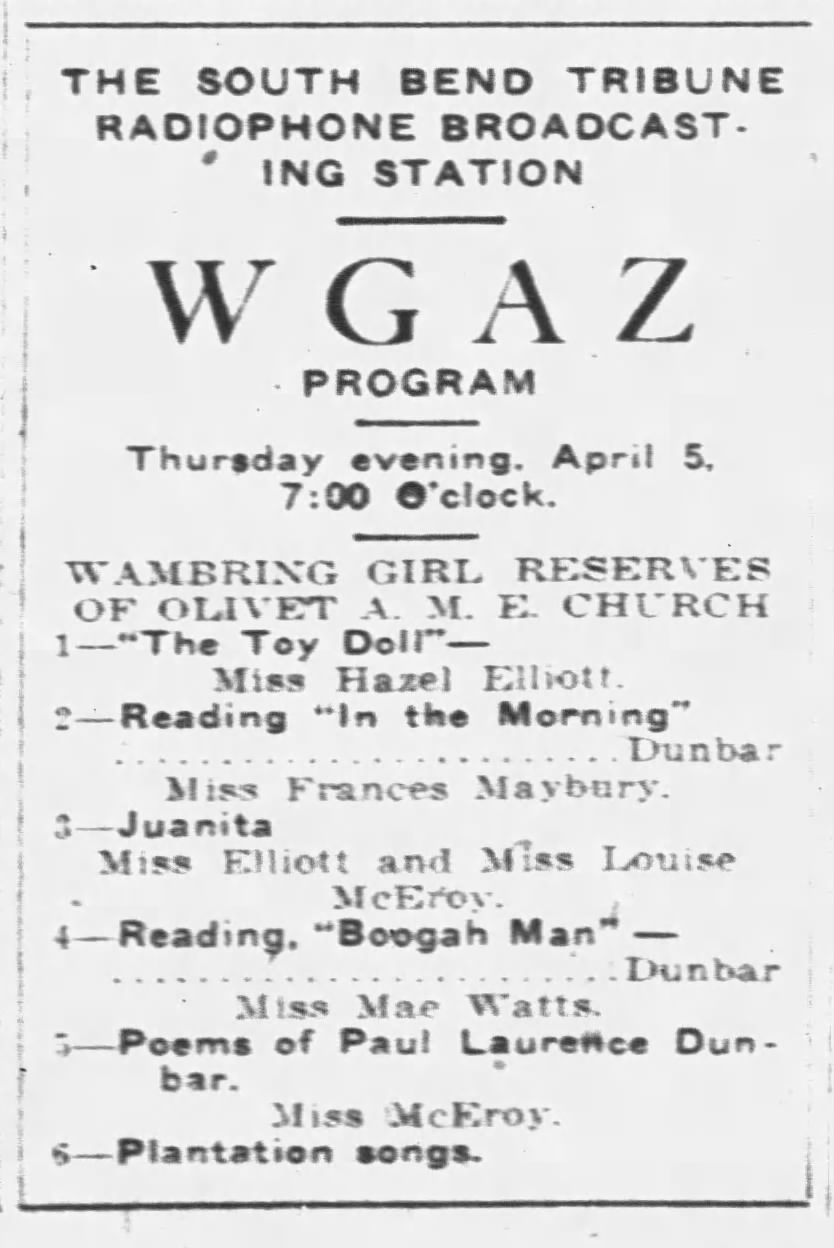

New technologies meant new opportunities to reach people, and Olivet’s leaders continually embraced them. As early as 1923, Olivet broadcast sermons and musical performances over the South Bend Tribune’s new “radiophone broadcasting station,” WGAZ (“World’s Greatest Automotive Zone”) 1350-AM—known today as WSBT 960-AM.

South Bend Tribune, April 5, 1923.

Several gatherings happened inside the parsonage—the home provided to the pastor by the Church. As early as 1883, pastors of Olivet were listed in city directories residing at the church on 310 West Monroe. This continues until 1915, when Rev. Allen is listed at 809 West Thomas (currently the site of the Studebaker National Museum). December 1920 marks the first reference of a separate parsonage just a few blocks away on 432 South Taylor Street.[13] Olivet’s pastors may also have found the home too small or in some other way too limiting, because in 1931 Olivet built a new parsonage on the same location, tearing down he previous structure. That parsonage remained home to Olivet’s pastors for over three decades until the move to North Notre Dame Avenue in 1969.[14]

From the 1920s into the twenty-first century, much of Olivet’s political activism was funneled through their support of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People—both the local chapter and other parts of the nationally revered advocacy organization. As early as 1921, Olivet hosted local chapter meetings. Several leaders served both Olivet Church and the NAACP, including the granddaughter of Farrow and Rebecca Powell, Medora Powell, taking on the role of NAACP Treasurer in 1924. As late as 2006, Olivet hosted a celebration of the national organization’s ninety-seventh anniversary. Pastor Rev. Franklin Breckenridge, who served Olivet from 2006 until his retirement in 2014, had been a member of the NAACP since 1954. Additionally, he served as state President for twenty-five years and on the national board of directors for twelve.[15]

Those entering Olivet’s Monroe Street entrance would have seen the Studebaker factory buildings (along with factory worker’s homes) a short distance to the south and west. However, in December 1963, the factory abruptly shut down. Over 7,000 people lost their jobs with hardly a day’s notice. City leaders scrambled to fill the void and figure out how South Bend would continue its monumental growth over the previous decades. As new ideas flowed for “downtown renewal” to chart South Bend’s path for progress in the rest of the 1960s and beyond, the 1917 church building was reportedly in the way of progress—considered by some to be an antiquated relic holding up potentially valuable redevelopment space.[16]

Olivet found a new home when, in 1969, another church congregation—the Lowell Heights Methodist Episcopal church—merged with the First Evangelical United Brethren to create what is known today as the Evangel Heights United Methodist Church. In 1924, Lowell built a new building at 719 North Notre Dame Avenue. After the merger between Lowell and First Evangelical, Lowell’s North Notre Dame Avenue facility became available.[17] Olivet purchased it.

On December 7, 1969, nearly one-hundred years after their founding, many of Olivet’s 326 members joined pastor Reverend Roderick Johnson to formally congregate their third church home.[18]

[CRHC.SBCRH.215] South Bend Civil Rights History collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center Collections, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

Despite the South Bend Tribune suggesting “the move was necessitated reportedly on account of the downtown renewal program which would ultimately involve that property,” the Monroe Street building never succumbed to the incredible changes surrounding it.[19] In March 1985, Mayor Roger Parent publicly announced plans for a new baseball field right next door (this turned out to be present-day Four Winds Field).[20]

Despite the potential threat to the original building, in 1986, a new congregation, Zion Hill Missionary Baptist, purchased the former Olivet building.[21]

During the late 1980s into the 1990s, dozens of surrounding homes and several factory spaces fell under a bulldozer to make way for what is now Four Winds Field and, in the late 2000s, Ignition Park. In 2018, a new apartment complex, the Ivy at Berlin Place, surrounded both the baseball field and, amazingly, still standing, the former Olivet building.

In the fifty years since moving across the St. Joseph River to worship at their third building, Olivet’s members continue their century-and-a-half tradition of being an open and welcoming space for worship. As a way of recognizing that incredible legacy, in July 2020, Olivet submitted an application for entry on the National Register of Historic Places that, as of this writing in early 2023, is currently under review and anticipated to be accepted. For over 150 years and in three separate physical spaces, Olivet continues to unite and enrich South Bend’s community.

[1] Program, Olivet AME 127th Anniversary Celebration. 1998,https://archive.org/details/CRHC.SMALL.227. South Bend Civil Rights History collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center Collections, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

[2] John Charles Bryant was a well known community historian and descendant of the Powell family. Farrow and Rebecca Powell were his great grand-parents, and John Charles grew up in the home they built near the original Olivet Church. John Charles’ frequently shared his encyclopedic knowledge of South Bend’s African American history as well as his ancestry, and in so doing ensured that the over 170-years of unbroken ancestry was known and celebrated. Regrettably, John Charles passed away on January 3, 2022. Like so many others, I owe John Charles a debt of gratitude for generously sharing his history, and for holding myself and other historians accountable to sharing facts accurately and caring about local African American history. I honor John Charles with these pages, and hope they meet his approval.

[3] “Early History of Olivet A.M.E. Church,” in, “Farrow Powell Reunion Program. 1998,” https://michianamemory.sjcpl.org/digital/collection/p16827coll4/id/670/rec/1 South Bend Civil Rights History collection, Civil Rights Heritage Center Collections, Indiana University South Bend Archives.

[4] “African Church Festival,” The South Bend Weekly Tribune. December 21, 1872, 2.

[5] “Sojourner Truth,” The South Bend Daily Tribune. October 6, 1873, 1.

[6] The South Bend Tribune. October 8, 1888, 4.

[7] A third, Rev. Casius Melzar Crosby, was born in Canada. See The South Bend Tribune, January 12, 1907, page 5.

[8] The South Bend Tribune. September 24, 1932, 2.

[9] “Tantsi to Talk About Africa,” The South Bend Tribune. February 1, 1933, 18.

[10] Rev. Dr. Allen became pastor in 1913. Rev. Evans served only until 1912, succeeded by Rev. B. Roberts who served only one year.

[11] “Congregation of Olivet A.M.E. Church to Have New Home,” The South Bend Tribune. April 8, 1916, 19.; “Final Service Planned,” The South Bend Tribune. April 22, 1916, 24.

[12] “To Discuss Meaning of Negro Migration Recently to North,” The South Bend News-Times. September 8, 1917, 5.

[13] The South Bend Tribune. December 22, 1920, 2

[14] Regrettably, the South Taylor parsonage does not have a happy end to its story after ending its use as a parsonage. A gentleman named Charles Taylor lived in the home beginning in 1970; however, he had several encounters with the criminal legal system. At some point between 1971 and 1973 the building was abandoned, and on August 10, 1973, it was consumed by a fire believed to have been started by arson. I am not certain if the house is torn down then or later when the entire block becomes parking for what is now Four Winds Field. See “Arson Seen In Vacant House Fire,” The South Bend Tribune. August 10, 1973, 23.

[15] The South Bend Tribune. March 12, 1921, 18; “Olivet pastor set to retire,” The South Bend Tribune. September 20, 2014, A4.

[16] “Olivet AME Church Sets Dedication Rite,” The South Bend Tribune. December 5, 1969, 28.

[17] “History, Evangel Heights United Methodist Church,” Evangel Heights United Methodist Church, accessed November 19, 2021, https://eheights.org/history/; " Denominations to Merge,” The South Bend Tribune. February 4, 1968, 23; “Lowell Heights Church, the Mortgage on Which was Burned Sunday,” The South Bend Tribune. July 13, 1903, 5.

[18] “Olivet AME Church Sets Dedication Rite,” The South Bend Tribune. December 5, 1969, 28; “Oldest South Bend Black Christian Community Has New Home,” The Reformer. December 7, 1969, 1.

[19] “Olivet AME Church Sets Dedication Rite,” The South Bend Tribune. December 5, 1969, 28

[20] Judy Bradford, “Ballpark kills church's plan,” The South Bend Tribune. December 1, 1985, C8.

[21] Jeanne Derbeck, “Downtown office plan given OK,” The South Bend Tribune. April 24, 1987, 13.